The ecology of the vegetation in the Cotswolds is strongly influenced by the underlying geology, which is a layer cake of limestone, sand and clay. High standing regions, such as Minchinhampton Common, and Cleeve Hill have a surface layer of harder limestone while the slopes down to the valleys often outcrop much softer rocks, which are easily eroded by streams.

Minchinhampton Common is therefore very well drained and is often surprisingly dry a few hours after all but the most persistent rain. The water quickly percolates down through the porous limestone surface layer. However, at some point it encounters a less permeable clay layer which forces it to move sideways. That is why there are many spring lines around the edge of the high standing ground, for example at Bubblewell (the clue is in the name). Even where the rocks are covered in surface soil, the experienced geologist can often work out where limestone gives way to sand or clay and vice versa just by plotting changes in slope and patterns of surface vegetation. Rabbits and badgers, of course, naturally prefer to burrow in the softer layers but welcome a nice solid limestone roof.

Where the springs and streams are not polluted they have a distinctive chemistry and ecology. Rain water is slightly acidic because rain drops pick up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so it dissolves a little of the limestone, producing a calcium bicarbonate rich flow. If fresh water plants in the streams then extract carbon dioxide from the water via photosynthesis, calcium carbonate precipitates in the stream as tufa coating bedrocks and even twigs with smooth stone. Tufa can be found in the Bubblewell streams (see marker on the Google Map).

This is a rare habitat. (N.B. Although a public footpath runs along side the gully where the tufa is found, there is no right to descend down to the stream banks. The access to the stream is, in any case, very difficult, and you are likely to cause damage to the environment and possibly yourself.) Tufa is found more extensively and can be seen much more easily in the stream running below the Strawberry Banks nature reserve between France Lynch and Oakridge Lynch in a site of international importance. Strawberry Banks is well worth a visit for many reasons, so go there instead.

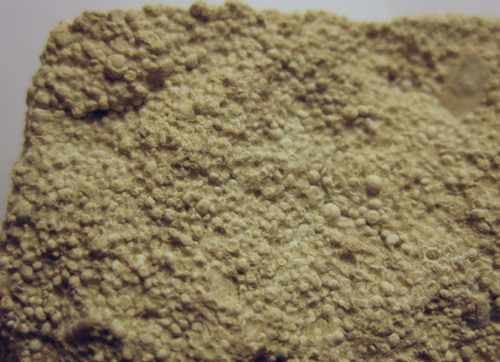

Much of the surface limestone is of a type known as Oolite. The name comes from the appearance of the rock which is supposed to look like a mass of small eggs. (In the image these are about 1mm in diameter.) We can deduce a lot about the conditions under which this rock was formed from this structure and some of the fossils found in the rock. For example, we know it was deposited in the sea, because we find sea urchins and brachiopods, which are never seen in fresh water. Furthermore, the water had to be precipitating calcium carbonate, so it was almost certainly a very warm sea, with lots of evaporation (and therefore also rather salty) rather like parts of the Arabian Gulf today.

It must also have been shallow, because the "eggs" are formed when gentle wave action continuously rolls tiny fragments of shell around, collecting limestone precipitate. (If you slice the rock carefully and put it under a geological microscope you can sometimes see the shell fragments. This link is an example of a thin section of Oolite from Minchinhampton.) In Crane's Quarry, in the middle of the Common, the exposed rocks show signs that the oolites have been swept into dunes by water currents. (This is much more apparent in other nearby localities, such as the quarries around Devil's Chimney, near Cheltenham.)

Oolitic Limestone

The same type of rock outcrops anywhere from Dorset (e.g. Lyme Bay) all the way up to the Yorkshire Coast (e.g. Whitby) and we know from the fossils that it was all laid down during about 165-168 Million years ago in the Jurassic Period (145-204 Million Years ago), when this part of the UK lay near the equator and just off shore from a large continent known to geologist as Laurasia, which had just begun to rift away from Gondwana to the south. And yes, a dinosaur has been found on Minchinhampton Common, when the reservoir was being excavated (the skeleton is thought to be in the Natural History Museum). However, vertebrate fossils are generally rare in this locality.

The local geology can be illustrated by this interactive map, supplied by the British Geological Survey, in which the layer-cake structure is very clear in the sides of the valleys. (You will need to zoom in to the location of Minchinhampton.)

British Geological Survey Map Viewer

Click on the map to find descriptions of the rocks.

Note that Minchinhampton Common is a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) since the quarries are considered to provide an important site for research into the Middle Jurassic in the United Kingdom, with extensive fossil faunas. (The Common is also a biological SSSI because of the unimproved herb-rich calcareous grassland, supported a wide range of flora and fauna. It is one of the largest commons in the Cotswolds.)

Fossils

Fossils are generally abundant in Jurassic marine deposits - though you will not find them in every layer. Limestone only forms when there is little input of mud from nearby river systems, and since rivers also bring nutrients and mud provides good places to burrow, life tends to be more abundant in such locations. Dead organisms also need to be buried fairly quickly (before something eats them) if they are to turn into fossils. Hence, fossils tend to be easier to find in the muddier layers. If you walk down through Box Woods you will find that some of the crumbly rock in the dry-stone walls seem to consist almost entirely of broken shells. Over on Rodborough Common, it is easy to pick up brachiopods as loose stones eroding out of the paths and impressions of large clam shells can also be seen in rock surfaces if you keep your eyes open. Sea urchins (also known locally as "pound stones" because they have been used as weights for scales) have been found near Winstones Ice Cream factory.

The image above shows (on the left) part of a sea urchin, while the other fossils are brachiopods from Rodborough Common. The smaller is from the order rhynchonellida - easy to recognise and name because of their wrinkly shells, while the larger smooth example is in the orderTerabratulida. Both orders are known to have living representatives and are articulate, a term which both describes the way the hinge works and also defines a major taxonomic division of the phylum Brachiopoda. (In death the hinge mechanism of articulate brachiopods tends to hold the two halves of the shell together, unlike inarticulate brachiopods such as linguilla where they are only held together in life by muscles and usually come apart at death.) They are sometimes knows as lampshells because (best seen on the example on the right) there is a small hole at the pointed end of the larger half of the shell from which a stalk emerged to act as a hold-fast to the substrate. Some people think this makes them look like Roman oil lamps. Brachiopods are a distinct phylum and should not be confused with bivalves which are in a completely different phylum (Mollusca).

Please note that because Minchinhampton and Rodborough Commons are SSSIs, you are committing an offence if you dig for fossils or hammer rock faces without a licence from Natural England. All of the above examples were picked up as loose stones lying on the paths.